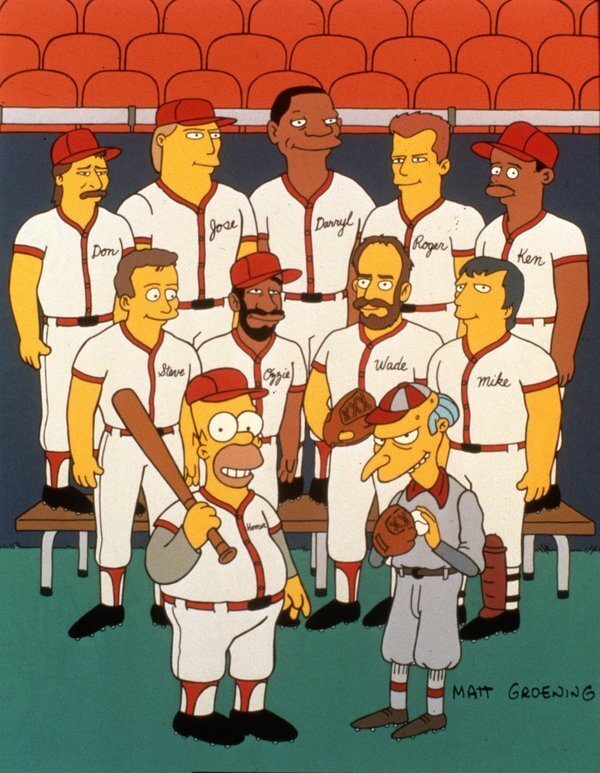

I maintain that The Atlantic built the newsletter-sector version of this image: A lineup of ringers, all.

When I saw The Atlantic taking in a whole slew of major writers under its brand name as a part of a major experiment in newslettering, I have to admit that I was happy to see a brand that big make such an ambitious bet.

But I also sort of felt like it reinforced a precedent around newsletters that wasn’t true when I personally started—Tedium came to life around 2015, nearly three years before Substack and two years before Revue—but has become increasingly true thanks to things like venture capital and mainstream interest.

And that is, simply, that people who already have big platforms are now being given all of the opportunities to move forward—at the cost of the little guy. (My pal Josh Sternberg, now of Morning Brew, had a great take on this point about a year ago.)

https://bsky.app/profile/shortformernie.bsky.social/post/3l7qpdid45w2o

I had a bit of a rant about all this, in which I compared this approach to Radiohead. Now Radiohead is a great band, and In Rainbows is actually my favorite album of theirs. But the groundbreaking pay-what-you-want model they came up with in 2007, which predicted the future success of Bandcamp and Spotify among other platforms, only really worked for them at scale early on because they had been so successful on a major label that they could afford to strike it out on their own and have a large audience follow along.

This is how many of the major newsletter success stories have played out—large audiences from media appearances, book deals, or high-profile jobs, parlayed into independent audiences, in hopes of getting full ownership of the final result.

The Atlantic’s approach is like an army of Radioheads because these people got the opportunity because of existing track records. It’s unlike Radiohead in one important way, however. These writers are giving something up in exchange for more stability: Their lists, which is a big risk, because if the model doesn’t work, they may find themselves having to rebuild a lot of work from scratch.

In a way, this is refreshing, because it at least feels like they’re not trying to kill the idiosyncrasies of these writers to fit this model. I will tell you that as someone who has been doing this for a while, this is not always the case.

In the past, when I’ve gotten close to career upgrade opportunities that came about thanks to my independent writing, I generally have said no to the ones I felt would harm my freedom in some way—and I didn’t get the upsides I might have gotten from those platforms as a result. One of those things was Substack. I was contacted by Substack about moving Tedium to Substack at a time they literally had two newsletters. And I said no, because they did not offer custom design capabilities (I see unique design as equally important to writing) and because I had gotten burned pretty badly a few years prior, when Tumblr failed to take any steps to assist its publishers in any way. Not all platforms are bad, but I wasn’t in the market to embrace one. I told them I liked what they were building and left it at that.

Now, did I know Substack was going to dominate the newsletter discussion in the way it has? Probably not, but I had an inkling they were probably going to change the space significantly. Honestly, it had a negative effect in the long run: Now people can’t necessarily win readers with an idea alone. They need a platform and a name, and building that from scratch becomes tough when you feel like you’re competing against Mr. Burns’ team of ringers from The Simpsons.

What happens if The Atlantic’s Newsletter experiment doesn’t work out.

More often, if opportunities have arisen in my case, the rub has usually been: We want you, but you have to retire your existing brand. Our brand matters more. Which is sort of like, why do I have to choose?

Not all opportunities are like this. For example, I have contributed to Vice’s Motherboard for more than five years, mostly with syndicated Tedium pieces. That has been great, because they aren’t trying to kill Tedium; they’re trying to raise it up. I know how rare that is, because I’ve been around the block a few times.

But I worry about folks who didn’t start before the trend really look off, like I did. Will they be able to stand out when their competition is made up of people who appear on CNN or have had bylines in The New York Times? Is the indie writer going to get overwhelmed by this state of affairs?

If I were the Atlantic, I would start up a farm system. Find the writer with a couple thousand followers and an underrepresented voice, give them the resources of The Atlantic, and help them shine. That will help the newsletter field more than building a team of ringers.

Time limit given ⏲: 30 minutes

Time left on clock ⏲: 1 minute, 30 seconds