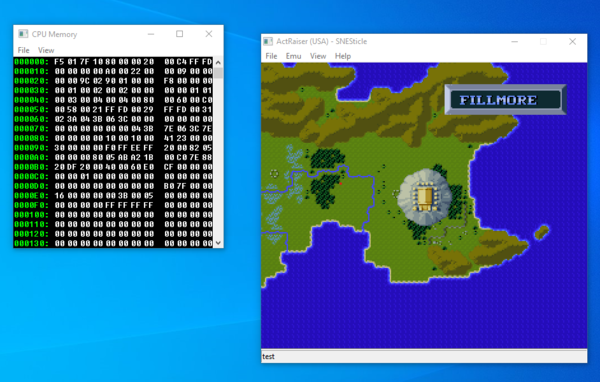

A screenshot of the Windows version of SNESticle, an emulator that did not see public release until last week.

In the early days of April 1997, I saw something that made me think completely differently about technology than I had previously, and in many ways, has put me on the writerly path I’ve spent much of my adult life working up to.

The thing I saw was NESticle, a Nintendo Entertainment System emulator that, while not first out of the gate, came to define this era of video games for me. Already a bit turned off by the push to 3D graphics, this felt like a more interesting path to me. It made me think about the mechanics of the games I played a little bit more, how they were built, and what they represented for technology. What the MP3 did for music, the emulator did for video games. It was a way to make an object digital, but also to keep it alive for generations to come.

Around this time about five years ago, I had the idea to try to capture everything I could about this time, this scene, these people, into a piece on NESticle, a tool that, when I was 16 years old, blew my mind. I wanted to understand why it came to life, the drama that slowed its growth, and the way that it changed video games and computing going forward.

So I wrote the story and talked to everyone I could from that period … except the man who made the emulator, who proved challenging to reach. (I had to make up for the gap with a ton of research.) But the story of what happened and how it changed video games nonetheless took on a life of its own. And the lore around this period continued to grow.

This week, it culminated.

The spark occurred as a result of a reverse-engineering effort involving a programmer who was just as inspired by this emulator as I was—and who wanted to see its barely released sibling emulator, SNESticle, live a second life. (In my original piece, I pointed out that it did, quietly, see a commercial release within a GameCube game.)

https://bsky.app/profile/shortformernie.bsky.social/post/3l7quycgqs72n

Icer Addis, the primary developer of these emulators, apparently saw the amount of work this person put in, and then quietly released the era-appropriate source code for SNESticle with a simple flick of the wrist and a simple quip. Most people did not even notice until yesterday.

“You guys have way too much free time,” he wrote of the ongoing interest in this emulator, which had not previously seen a standalone public release. (Now it has one, complete with a permissive MIT license.)

And it’s weird. To see this happen, as simple of a gesture as it might be at this point, feels like it closes a chapter on a tale that for much of my adult life I’ve been inspired by and that I think a lot of other people have, too.

These emulators helped us relive stories and learn new things about the games we loved. That we get to learn something new from one of these groundbreaking emulators makes it feel like we’re coming full circle.

Time limit given ⏲: 30 minutes

Time left on clock ⏲: 21 seconds