(Dan Gold/Unsplash)

Let me preface this by saying I’m a terrible cook. I am not particularly great in the kitchen, though I have learned some techniques over time. I know one (1) decent recipe for scrambled eggs. And more often than not, I burn my bacon by leaving it in the oven too long (my technique: cooking on parchment paper). My bread-making capabilities are nonexistent, and my attempts to make chocolate chip cookies from a recipe sometimes end up a lot more like muffins than cookies.

My wife and I had a longstanding debate over whether or not we could have a microwave. Guess which side of the debate I was on.

But I do care a lot about copyright issues and find the debate on them really interesting. And recipes have an unusual place in that debate: Mainly, they don’t have one, because they aren’t technically covered under copyright law. As Copyright.gov puts it:

A mere listing of ingredients is not protected under copyright law. However, where a recipe or formula is accompanied by substantial literary expression in the form of an explanation or directions, or when there is a collection of recipes as in a cookbook, there may be a basis for copyright protection. Note that if you have secret ingredients to a recipe that you do not wish to be revealed, you should not submit your recipe for registration, because applications and deposit copies are public records.

(James Lee/Unsplash)

This explains a lot about online recipe culture, including why storytelling and recipes are so tightly tied together. A recent New York Times story laid out how this limitation to the copyright law, basically existing since the beginning, has helped to create a culture where the fear of theft discourages some cooks from sharing their recipes. And the roots of the problem speak to outdated perceptions from the colonial era:

When the nation’s copyright law was first codified in 1790, cooking was seen as a woman’s domestic responsibility rather than as a professional activity, [intellectual property lawyer Sara] Hawkins said. Written recipes are a relatively new invention; many cultures passed down culinary traditions orally.

While the technology and music industries have pushed successfully to change copyright law in their fields, “there is not a big powerful lobby to push anything through for individual recipes,” she said.

As a result, some cookbook authors feel less willing to publish their treasured recipes.

In some ways, this point does make sense; a list of instructions may seem less like creative output than, say, a guy writing 30-minute rants against a timer, despite the fact that the list of instructions took a lot more work. (See what I did there?)

But now, recipes are big business, and a successful cookbook can raise a chef’s profile in a big way. And there are notable cases of cookbooks being full of pilfered recipes, complete with stories, which are often necessary to help protect the copyright. The Times story highlights how a high-profile chef, Elizabeth Haigh, had her book removed from shelves after a lower-profile author, Sharon Wee, pointed out that her recipes and even her personal anecdotes were pulled into Haigh’s book.

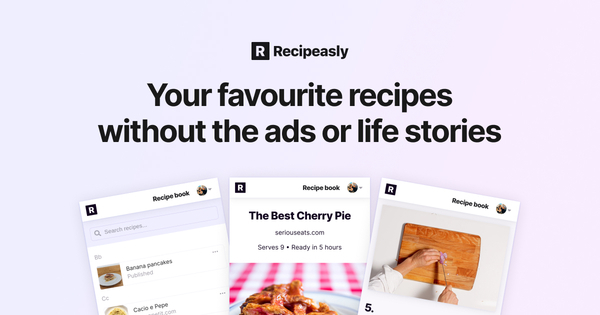

Your content, without any of the work that makes it yours. (Recipeasly)

But at the same time, there is probably a case for the law to change at some point, especially as the internet changes the nature of cooking. A case earlier this year highlighted just how messy things could get: A startup named Recipeasly attempted to “fix” online recipes by removing 1) the ads and 2) the stories that preface the recipes. The stories are there because they’re important for SEO as well as the previously explained copyright reasons; the ads exist because people don’t want to work for free.

Recipeasly attempted to simplify the process, and found itself shouted down by the food world in short order. While they technically weren’t breaking the law by simply listing recipes, they had crossed an ethical red line, and got called out for it. The site quickly shut down.

Should recipes be copyrighted? And what do copyright protections look like for something that can be creatively altered by anyone? A complex question. But one could argue that the current law doesn’t do nearly enough to resolve.

Time limit given ⏲: 30 minutes

Time left on clock ⏲: 1 minute, 2 seconds