Mastodon may not go extinct, but will its existing culture? (peebot/Flickr)

OK, we’re on week two of the Mastodon pop-up, and I just want to thank everyone who signed up for this newsletter in the past week to follow along, or shared it with their audiences on Mastodon or other platforms.

This has been a fun change of pace for me, even if I likely won’t be doing it permanently. That said, I’m thinking about a way to give people the most out of this discussion so they feel like they are well-equipped for this strange new world, and I think in many ways, culture is the way to go.

The technical parts are the technical parts, but the culture is the element that requires some adjustment. And with that in mind, I’m focusing today’s issue on one of the most common refrains about the elephant site: that it’s in the midst of an Eternal September.

I don’t agree, but there are some elements that are worth discussing, so let’s get to it.

Cultural Pulse Check

Not an Eternal September, an Infernal September. (Marco Verch/Flickr)

The case that Mastodon isn’t really facing an Eternal September but something entirely different

So, if you’ve spent any amount of time on this social network of late you have most likely noticed people talking about the idea of the Eternal September, and how Mastodon is facing one.

For those not familiar, the Eternal September refers to a concept from the days of Usenet when, after years of new students stinking up the place at the beginning of each fall, the order of the ecosystem was forever broken when AOL connected its member base to Usenet.

And it makes sense that this conversation is coming up. After all, when a flood of new people come in, it can threaten to deeply change the makeup of a given community no matter what steps that community might take to protect its norms. (Additionally, as I mentioned last week, Mastodon is structured very similarly to Usenet, which at its core is a list of discussion groups, often without moderation.)

Now, it turns out that I have actually researched and thought about the topic of the Eternal September a lot in the past. I’m honestly of the opinion that there was only one of those, and the exact circumstances were unique to its moment, and that those reverberations ultimately were felt across the entire internet, even decades later.

In effect, the Eternal September was a form of gatekeeping. It discouraged these new users from getting too close or from learning too much about the more technical aspects of what was being discussed there. And it created a dynamic where people unfamiliar with a topic were uncomfortable with asking, one that persists on technology forums to this day.

There are a few key differences, however, between Mastodon/the broader fediverse. In 1993, Usenet had no way to batten down the hatches, really, because most of the groups were unmoderated. But in the case of Mastodon, there are much more powerful controls at play that create a significantly different experience. If you want to block a user’s entire domain, it is possible in Mastodon from the notifications menu. You could, technically speaking, shut off your instance from the entire world, recreating an effect not dissimilar to M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village. (Sorry, I just spoiled that movie, but it’s been out for 18 years, so hopefully it didn’t hurt too much.)

The differentiator here, I think, is that the new users coming to Mastodon are by and large coming here by choice, and I think that the various communities, for the most part (as the fediverse is not a singular hive mind), aren’t necessarily opposed to the addition of new users. After all, Mastodon was specifically built to be an alternative version of Twitter, which means that in some sense, getting people to come from Twitter to an alternate platform was ultimately the goal.

Kye Fox, one of the users I’ve gotten to know a bit better in recent weeks since the recent pop-up in interest in Mastodon first came to life, came up with a new phrase to describe this state of affairs: It’s an “Infernal September.” For the most part, the old-timers want you here—as long as you make room for them. But because of the complex nature of norms, it’s very much a trial by fire, so don’t be surprised if something is lost in the process.

On Friday, I caught a user with a large profile transitioning over from Twitter essentially saying that, because primary developer Eugen Rochko made the case that content warnings weren’t used consistently across platforms, he would not use them. But on top of that, he said he would ignore any complaints about them. And given that he blogs almost exclusively about politics and has more than 100,000 followers on the bird site, this means end users are stuck having to adjust to his feed, rather than the other way around. I lightly chided the guy to have some compassion for the existing user base, and he blocked me.

That to me is the real risk right now—that people who don’t care about the norms of a new community will just barge in and expect us to bend to them. That’s different from an Eternal September. That’s a trial by fire.

The real risk is whether or not anything might be left in the end. Tim Bray, the former AWS executive who left in protest of the parent company’s stance on whistleblowers, has pointed out there may be real challenges to keeping that culture alive:

I respect unique online cultures. But there’s maybe a problem. If Twitter does implode, Mastodon could very quickly gain a whole bunch of new users, to the extent that long-term Mastodonians are like only 1 percent of the population, and the newer 99 percent has no appreciation of nor interest in “Mastodon culture”. The system is flexible enough that maybe there’s scope for an “og-mastodon” instance that would work in a more traditional way?

There have been some that have compared Mastodon to a Twitter with homeowners associations, and doing so while citing the most extreme examples. (Of course an academic community is going to have high moderation standards!)

But it’s worth pointing out that there are many neighborhoods, and you are given a choice as to which one makes the most sense for your needs or interests.

I guess what I’d say here is that making a new community work is a two-way street. Don’t be afraid to put a little work in.

Tips & Tricks

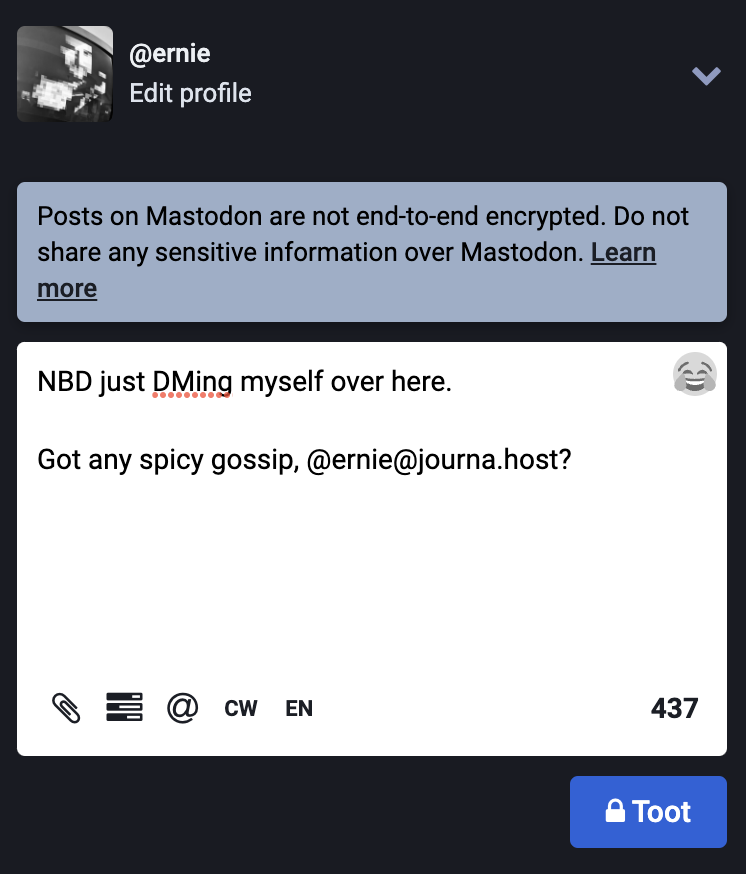

An example of what a DM looks like on Mastodon.

Don’t share your credit card number: A few direct-messaging differences to be aware of

Of the many things that you might run into on Mastodon that is distinctly different than Twitter is the private messaging function. It exists, but it is not the same as Twitter’s function, in part because it is not quite as secure, and its differences can create some potential awkwardness.

For one thing, adding someone to a DM group is as easy as simply mentioning them. But that means that if you’re having a conversation about a third person, if you mention them, you’ll suddenly find your criticism exposed to them, which means that your backchannel is in threat of getting awkward.

And for another, DMs take place in the same pool as every other conversation, making it a little hazy when the public conversation ends and where the DM begins.

There’s also the concern of your admin having the ability to read your DMs, which … let’s face it, is probably also true of Twitter. Be mindful of how you use DMs on non-encrypted platforms.

Dell Cameron, a Gizmodo editor who has been doing some great work around these parts for a little bit, has a great guide up for determining when to use a direct message on Mastodon.

As with Twitter, there is no end-to-end encryption, so if you’re talking serious business, take it to Signal or a burner phone.

Links & Stuff

» Get a handle on your second factor. If security is an issue, it’s worth noting that Mastodon has robust second-factor authentication capabilities that don’t rely on the less-secure SMS. Sam Schlinkert, a longtime Mastodon user, has a great guide on setting it up.

» If you’re looking for a Mastodon server that’s hosted and managed by a company with a generally good reputation, the web browser Vivaldi recently launched an instance that allows users of that browser to sign with their existing login, meaning that the onboarding process is easy.

» A good strategy for finding your community from the admin of the activism.openworlds.info instance: Follow a lot of people, then cull out the boring bits as you find the most interesting ones.

One Killer Take

Joshua Topolsky, a key figure in the creation of at least three popular technology sites, posted something on Friday that helps to reinforce the general idea I was discussing above—that this is an opportunity to reset our approach to social media.

Just turning Mastodon into another Twitter will lead to the same results in the end, if maybe fewer rocket enthusiast owners.

Alright, that’s the end of issue four of How To Mastodon, a pop-up newsletter hiding inside of MidRange. Follow me on Mastodon for more insights and tips, along with all the other weird stuff I’m interested in. MidRange will be back next week!