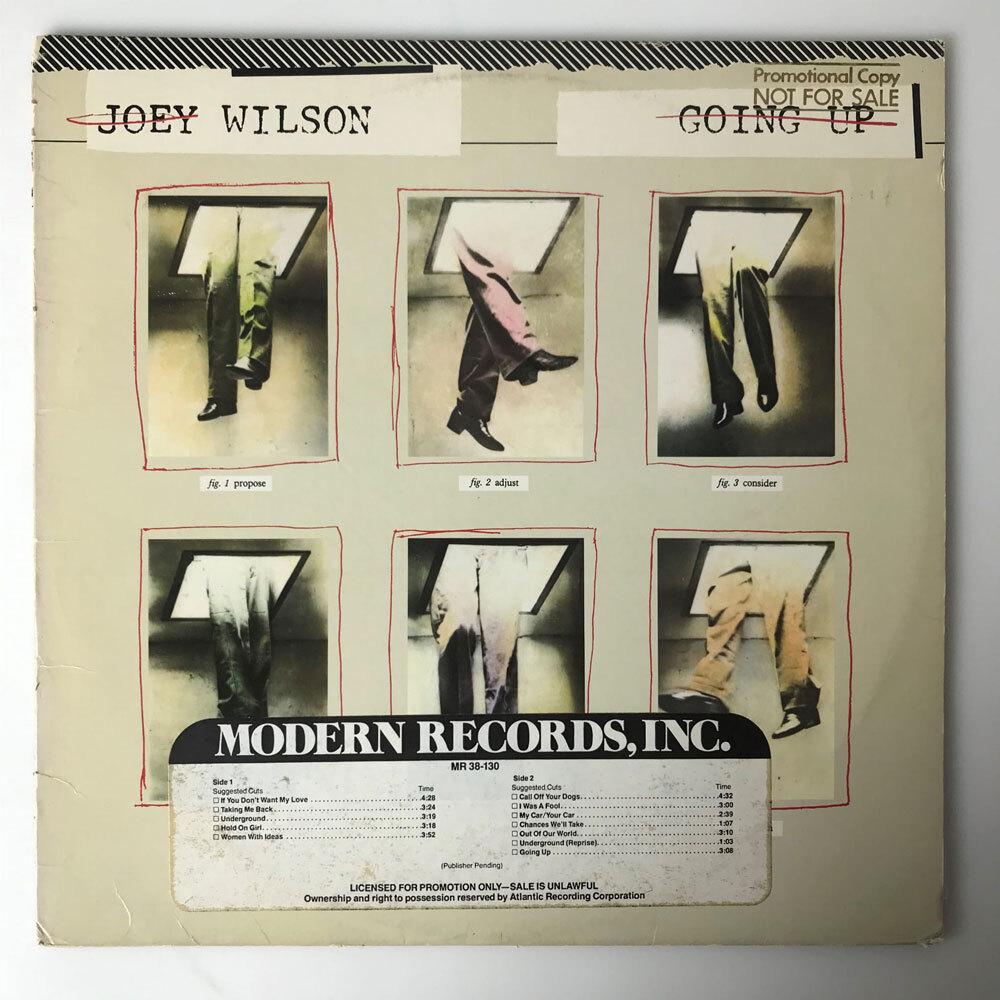

“Going Up,” an album you probably have never heard of that you’re going to learn a lot about after reading this piece.

Ever have an earworm stuck in your head that you know barely anything about?

Welcome to my world over the past week. I kind of have to credit/blame the Internet Archive’s Jason Scott for this, admittedly. While digging through the archives of late video producer Mark Pines, he uncovered a music video for an artist that was unknown from any of the given information, which he then posted on YouTube.

I heard this song and couldn’t stop thinking about it. Arguably, the lyrics are a bit on the cliché side of things, but the music was extremely grabby, with the use of strings to really pull at you in a way I might compare to Rodriguez’s “Sugar Man.” Pines’ music video, showing a singer with a voice that cuts halfway between Elvis Costello and Buddy Holly and a pencil-thin mustache not far removed from John Waters, was all listeners had to go by.

After Jason posted the video, I started doing a dive on my end to see if the lyrics pulled up any positives. Not really, in part because there were more than a few cliché phrases in the tune. Eventually, though, someone recognized the keyboardist in the music video, and boom, we had some details on the music and the artist.

I’m writing the story here as a courtesy to anyone who, like me, heard this song and was blown away, and wanted to know something about this song and the musician who wrote it.

Joey Wilson was a New Wave singer who came up out of the Philadelphia music scene in the early 1980s, mostly playing folk music at local venues until he decided one day to switch it up and move to an electric guitar, essentially on a dare. He quickly gathered together a band and started playing shows as a solo artist. Within a couple of months and with just a handful of shows on electric under his belt, he ended up getting signed by a new record label, Modern Records. The label, led by music industry notables Danny Goldberg and Paul Fishkin, was effectively a boutique label with distribution through Atlantic Records, and Wilson was the first artist signed.

“I liked the idea of going with Modern,” Wilson said in a 1980 interview with The Philadelphia Inquirer. “It’s a small label. Right now I’m the only act, and the plan is that they won’t have any more than three acts at one time. So you know that the label will be doing everything it can to help.”

Wilson, who the paper noted was a Tony Bennett fan, had some solid pedigree behind him. The producer on his solo album, Going Up, was Jimmy Destri, the keyboardist for Blondie during its most popular period. Destri’s work on the album apparently gained him some notice, with U2 apparently impressed enough with his work that they called him up and nearly hired him to produce what would become their breakout record, War. As a U2 fan site noted, Destri had this to say about the opportunity:

Right after Blondie broke up, I produced the first album for Danny Goldberg’s label, an album by Joey Wilson called Going Up. It was a big hit in Billboard and Joey went immediately into AA. Danny went on to become this big media mogul. Because of Joey Wilson I was invited to produce “War”, the U2 record with Steve Lillywhite.

Destri never produced War, but the band did get a couple of recordings out of their work with him, including some ideas that were later used on The Unforgettable Fire.

But as for Wilson, while he got some early buzz for the record, it ultimately went nowhere. Danny Goldberg ultimately turned Modern Records’ focus on the artist that he started the label with—Stevie Nicks, whose Bella Donna would soon be a huge seller for for the label.

“We changed our game plan. We looked at our bottom line and tried to project our future bottom line and decided that, for the time being, what we had to do was concentrate solely on Stevie,” Goldberg said, according to a press release from the label. ”I mean the difference between selling 1 million or 2 million albums on a superstar makes a good deal more sense than 20,000 or 60,000 on a new act. While we both love the creative aspects of breaking new acts, we want to stay in business first.”

(Goldberg would later start a company that managed a number of famous bands, most notably Nirvana.)

So where did that leave Wilson? Ultimately, he returned to Philadelphia, where he ended up starting a number of other bands, the best known being Youth Camp, a band that included members of The Hooters (a Philly band that did make it to the big time).

While Youth Camp never broke beyond Philly like The Hooters did, Hooters and Youth Camp drummer David Uosikkinen, later a cofounder of MP3.com and a local legend in Philly, always spoke fondly of his time playing with Wilson.

“He’s probably as brilliant as an artist of taking that emotion and putting it into words,” Uosikkinen said in an interview posted to YouTube in 2010. “You know, I mean, the guy was the funniest guy. I don’t know if people really knew, but he was just hilarious.”

As you might have figured out from that description, Wilson is no longer with us. As explained in a 1998 Philadelphia City Paper article linked on Discogs, he died on Christmas Eve, 1997, of a heroin overdose, at the age of 43. And while he never became a truly big star, he remained active in Philly’s local music scene until the end of his life, with his last recorded performance taking place in 1996. The pencil mustache was gone, but the musical skill was still there.

I watch these videos of Wilson and listen to “Underground” and I hear a guy who all too easily could have become a star in his own right. He was closer than most. He was labelmates with Stevie Nicks, and had his album produced by a member of Blondie. He had some killer songs, and his own friends back in Philly were having the breakout hits that he, sadly, did not.

I should point out, again, that “Underground” is a great song. It rules. And there was a reprise of the song on Going Up, the full album for which is available on YouTube. It feels like the perfect way to end this post. I hope people read this and give Joey Wilson a listen. It would be great if this man had a little rediscovery because of an unlabeled recording uncovered by the Internet Archive.

Time limit given ⏲: 30 minutes

Time left on clock ⏲: 17 seconds, but with more polish than usual during the edit