(sadaqah/Flickr)

As I’m somewhat on the Cheetos beat, having written a key document about the history of extruded corn snacks (a tale that is backed up by actual patent records, I should note), I have to admit that I always found the tale of Richard Montañez interesting from a distance.

Montañez, a onetime janitor for Frito-Lay, claimed to have come up with the recipe for Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, a famed combination of spice, dye, and extruded corn that proved a popular treat for any streetwise fifth-grader. This led to his rise up the ranks at Frito-Lay to a leadership role.

This was the kind of story that sites such as CNBC ate up, as it reflected a lot of important things—it was a tale of perseverance, and a tale people could point at when looking for a Latino success story in the business world.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do. Didn’t need to. But I knew I was going to act like an owner,” he said of his invention during a 2014 event, according to The Washington Post.

https://twitter.com/GustavoArellano/status/1393966501296705543

Just one problem, as pointed out by the Los Angeles Times over the weekend: He didn’t actually invent the product that he claimed to invent.

In a deeply reported story on the neon-red snacks that would be a bad idea to eat if you’re a hand model, staff writer Sam Dean reveals the depths of an embellishment that could have a significant impact on a forthcoming Hollywood movie. Rather than being devised by a low-level employee who was working as a janitor, the product came about in a more traditional way—simply, market research found that regional brands were seeing a lot of success with spicy snacks, leading to the formulation of a new competitor, and a new-to-the-business employee with an MBA from the University of North Carolina did the hard work of building the branding.

(In a somewhat smaller bit of fibbery, Montañez also did not spend very much time as a janitor before getting a promotion in the factory.)

The bummer about this is that, beyond this trumped-up invention, Montañez had a perfectly worthy career arc, finding himself in a management role after starting off in a Frito-Lay factory—but he apparently felt compelled to kick it up a notch.

“Montañez did live out a less Hollywood version of his story, ascending from a plant worker to a director focused on marketing. He also pitched new product initiatives, which may have changed the path of his career,” Dean writes. “But Montañez began taking public credit for inventing Flamin’ Hots in the late 2000s, nearly two decades after they were invented.”

That led Montañez to gain a successful career as a public speaker, and later to the movie deal that was about to turn this story into something way bigger than it would have been otherwise.

Frito-Lay, for its part, was careful about trying to thread the line between honest success story and over-the-line claims, sending this statement to Dean: “We value Richard’s many contributions to our company, especially his insights into Hispanic consumers, but we do not credit the creation of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos or any Flamin’ Hot products to him.”

This is a sad state of affairs, and one that just feels like a bit of a loss for everyone involved, including Eva Longoria, who was set to direct this film. But it reminds me of the story I wrote just the other day about Phar-Mor, the pharmacy retail chain that decided it was better off cooking its books to keep up the illusion that it was about to destroy Walmart, rather than the truth that it was a fast-growing chain that deserved its flowers, even if it couldn’t actually undercut Walmart without going in the red.

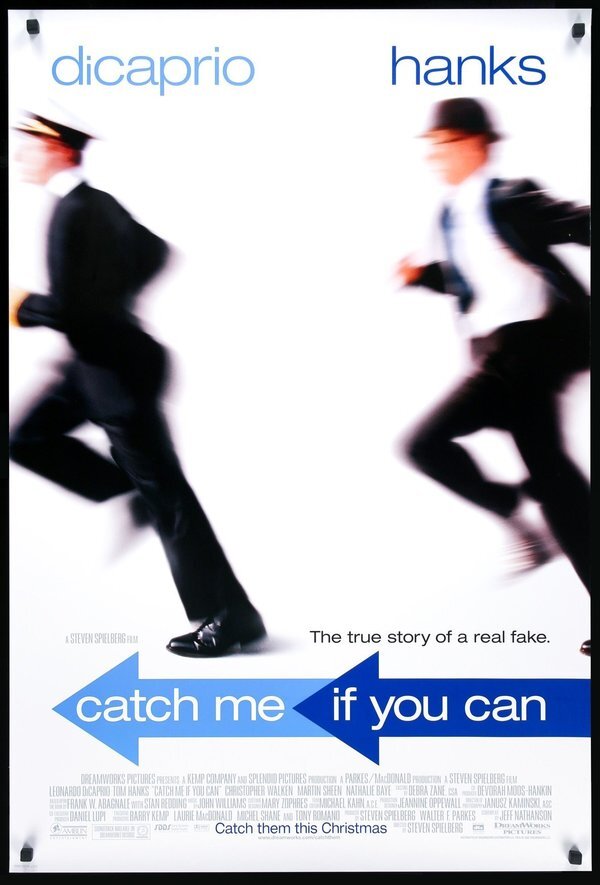

Montañez had a perfectly compelling story on its own, but it was not so compelling that it could overtake Hollywood. That leap of faith is generally what drives great movies such as Catch Me if You Can—the storyline for which is not very much like the book it’s based on, and is currently facing very similar scrutiny from a reporter who actually did the digging to confirm what was and wasn’t true.

I guess the lesson here is this: If something sounds too good to be true, actually dig into the archives and confirm it yourself, especially if you’re a film producer.

Time limit given ⏲: 30 minutes

Time left on clock ⏲: alarm goes off (technical issues)