Shout-out to the fellow members of the Mario’s Picross cult.

Back in the mid-’90s, I quietly gained a strong affinity for a Game Boy game called Mario’s Picross, which essentially was a series of logic puzzles that encouraged the player to put dots into the correct place to draw a picture, pixel by pixel, based on numbers listed on a grid.

This kind of game was one of many puzzle games of its kind back in the day, and it was actually much more rare in the U.S. than Japan. It’s not one of Mario’s best-known titles, but it was one of the few appearances of the nonogram, the puzzle type picross is better known as, outside of Japan.

Named for Non Ishida, a graphics editor who is one of the two people credited with creating the puzzle style, it started out as a paper-based phenomenon in the late 1980s before quickly going electronic, basically as if Tetris and pentominoes had been developed in the same decade. From there, it became a cult style of game—never as popular as, say, sudoku, but definitely appealing to that same type of player. Mario’s Picross, which has somewhat recently appeared on the Switch, has a bit of a cult following these days, being a poor seller on its initial release. The developer of the game, Jupiter, has found more success with Picross-style games on other platforms, though I haven’t really played a portable Nintendo console in quite a while.

Great game, but this would be a better game without a timer, if you ask me. (via Super Mario Wiki)

For years, I forgot about Picross, but then found myself playing again when I got a Game Boy Advance emulator on my iPhone, which led me to play the Japan-only sequel Mario’s Picross 2, which I slowly made it through on a trans-Atlantic flight I made a few years back. Despite not being able to read any of the dialog boxes, I beat it handily. It was a source of quiet joy during a stressful time.

The problem with me and games is that if something is too addictive, it can kind of threaten to take over my life, destroying my productivity; I need something that I can play for a little bit, set aside for a few days, and come back to at my leisure.

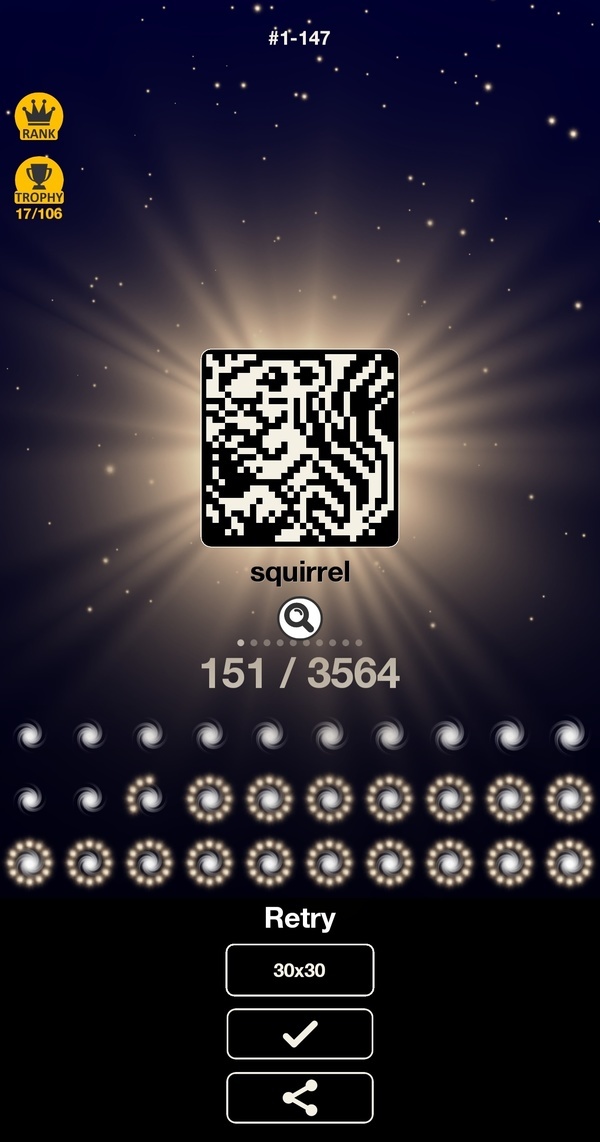

This picture of a squirrel, drawn on a 30x30 grid, was particularly tough.

Over the last few months, I’ve been playing more of this type of game—particularly in the form of Nonogram Galaxy on my Android device—and I find it to be a very calming and mind-sharpening tool. It’s not high-action, but it requires your brain to do a lot of quick math, especially when the puzzles get very complex, with dozens of individual pixels. It’s puzzle-solving, but not overly flashy. I have completed 151 puzzles on this game so far, which is a lot given the complexity of the puzzles, but there are more than 3,500, so I may never need to play another game ever again.

One small difference between this game and Mario’s Picross is that it does not punish you for messing up or put you up against a timer as you play, which I think is actually a much better experience at a time when I think a lot of folks are looking for ways to calm down without a lot of additional stress or addictive elements. (I would recommend paying for the no-ads option though, because once you finish a puzzle the ads can pull you out of your spot of zen.)

Not all games need to be life or death. Sometimes they’re best suited for encouraging you to stay sharp.

Time limit given ⏲: 30 minutes

Time left on clock ⏲: 1 minute, 21 seconds